Published in the March, 2009 issue of the Biscayne Times newspaper:

Photo by Silvia Ros

Not far from Biscayne Boulevard, outside his ramshackle home just north of the 79th Street Causeway drawbridge, Omar Ali is slumped in a folding chair, his thin frame draped in well-worn canvas work clothes, his face turned toward the sun. He’s listening to Classical FM radio over a pair of loudspeakers, fidgeting with an unlit cigarette, and watching an osprey obsessively circling the sun-sparkled waters of Biscayne Bay that stretch before him.

The bird swoops down, talons outstretched, and with a soft splash, snatches a fish from the water. It rises, shakes off the water from its plunge, and glides over to a rotting wooden pylon to feast on its writhing prey. Ali smiles. He lifts the cigarette to his mouth, almost lights it, but stops. It’s the holy Muslim month of Ramadan, smoking is forbidden during daylight hours, and he’ll have to wait until sunset to break his daily fast.

But the 54-year-old Egyptian metal sculptor isn’t focused on his hunger or nicotine craving right now. He’s mostly thinking about the five-ton, stainless-steel sculpture towering 25 feet over his head, casting a strange, twisted shadow over his Shorecrest property and, more figuratively, over his life.

Back in 2004, he designed and built the mammoth piece — a graceful, spherical tribute to the famed French explorer Jacques Cousteau — for a local real-estate developer named Riccardo Olivieri.

Ali’s tribute to Jacques Cousteau awaits a buyer, perhaps in Abu Dhabi.

Olivieri planned to install the work at the eastern entrance to the MacArthur Causeway, as part of his twin-tower condo development named the Bentley Bay, in full view of the tens of thousands of motorists who careen daily across the busy thoroughfare. With such prime skyline positioning, the installation would have been one of the area’s most prominently displayed sculptural artwork and would almost certainly have become a local landmark. And of course, the exposure for Ali as an artist would have been unparalleled.

But five years later the sculpture is still here, looming above Ali’s one-story home, rather than overlooking one of the South Florida’s busiest bridges. Ali reaches for a folder, pulls out a sheet of paper, and holds it up. It’s a court document with a judge’s signature at the bottom. “They bought the piece for $85,000,” he says dryly, “and sold it back to me for nothing.”

The path that led up to, and then veered sharply away from, artistic success was a long one for Ali. He’d like to think he’ll still get another shot at a high-profile installation. For now, though, he’s eager to tell the story of his abandoned sculpture and of all the legal wrangling that came with it.

Not many people know the reclusive Ali or of his fierce brand of metal work. He doesn’t leave his house much, he rarely exhibits, and most of all he doesn’t like to be separated from his tools. In fact his home and his studio are one in the same — a shoddy former boat-repair yard and work shed that he converted into a makeshift home. Roll-down metal shutters serve as doors, the exposed concrete walls are lined with metallic sculptures and tools, and the unairconditioned bedroom he constructed in the back sits so close to Biscayne Bay he can hear the water gently lapping the seawall as he falls asleep at night.

The Cousteau sculpture as it would have appeared at the Bentley Bay.

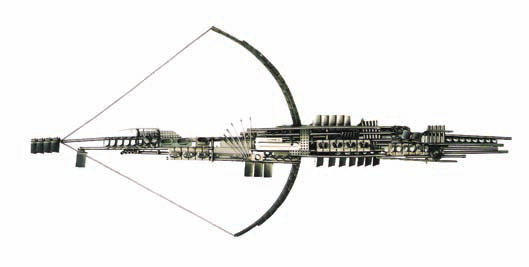

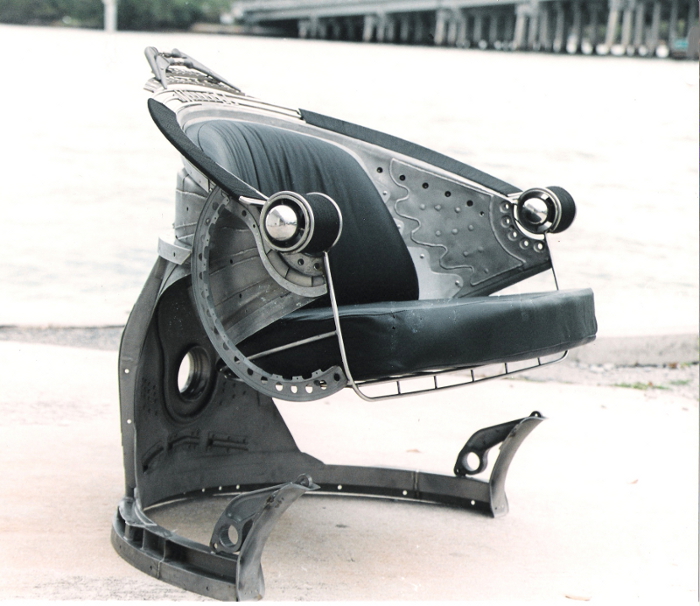

Ali spends his days drafting intricate designs, occasionally heading out in his 1989 Chevy pickup to scavenge for airplane and military parts at scrap yards along the Miami River or at military and government auctions. The titanium and stainless steel, of which those parts are often made, are Ali’s metals of choice. He doesn’t build. He “engineers” precision sculptural objects that are as elaborate in design as they are formidable in construction. Chairs, benches, floor lamps, table lamps, animals, abstractions — most of his pieces look like something between art and artillery. (For examples, visit http://www.artaircraft.com.)

“The best metal is airplane metal,” Ali explains. He turns jet engines into chairs, wings into benches, turbines into tables, fuel valves into lighting fixtures, steel tubing into faux machine guns. “But I don’t consider all of that art,” he concedes. Well-designed functional pieces, like furniture, are just easier to sell. And as for the machine gun, he traded that to a local mechanic for $5000 in repair work on his old truck.

“Real art delivers a message,” he contends. Art is the 11-foot great blue heron spreading its titanium wings on Ali’s concrete terrace. Art is the metallic fish (a grouper?) whose graceful curves follow the aerodynamic arcs of stainless-steel aircraft parts. Art is the sundial he’s crafting from a DC-9 engine to commemorate the crew of the space shuttle Columbia by directing a single beam of sunlight onto the name of each astronaut at different hours throughout the day.

Ever since Ali was a boy in Cairo, his creative tastes have leaned toward the industrial, the mechanical, and especially militaria. “My father was a genius with his hands,” he recalls. A mechanic by trade, Ali’s father would scour Cairo for old automobile parts, refurbish them, and assemble large, fortified work trucks, which he would later sell.

Forklift Ant with driver’s seat.

Ali quickly began to mimic the old man, building his own toys in a similar fashion. He’d rig small electric motors to empty tomato cans to make toy cars. A neighbor in uniform influenced him, too. “There was a military guy in my building,” he recalls, “and every morning soldiers would come pick him up in a big, brand-new Land Rover. I fell in love with that car and with everything military.” Eventually Ali started using his father’s tools to make mini tanks instead of cars.

But at age 17, seeing no future for himself in his impoverished homeland, he obtained an Italian tourist visa — the easiest and cheapest visa Egyptians could get in the 1970s — and headed for Rome. Circo Nones Orfei, an Italian circus, recruited him at Rome’s main train station on his very first day in the country, the station being a popular hunting ground for immigrant labor.

“I cleaned up a lot of animal dung in the beginning,” he says. With time, and once he had learned enough Italian, the circus manager upgraded him to helping care for the elephants and creating promotional artwork. “Italy was paradise,” he remembers. “I spent four years with the circus and saw the entire country. But there were a lot of dangerous people in the circus — criminals, lunatics, all kinds.”

Tired of the vagabond lifestyle, Ali settled in Milan in 1976 and began to concentrate on his art. He rented a machine shop and began experimenting with leather and jewelry, churning out purses, belts, amulets, and lockets. Functional metalwork like lamps, gates, windows, and doors helped to pay the bills, too. In his free time, he began sculpting, exhibiting widely and even enjoying extensive coverage in Italian newspapers. But, he says, the country experienced an economic downturn in the 1990s and it became increasingly difficult to make a living. Ali could no longer afford his rent. He lost the workshop, sold his tools, and after 28 years in Italy, packed up and headed for Miami on the advice of a friend who had already emigrated.

Light Fixture.

“In 1999, when I arrived, Miami was beautiful,” Ali recalls. “The lifestyle was free and everything was easy. I managed to get a work permit, found some decent work here and there, and bought my house.” Notable among his projects, he created and installed the metallic interior of Jail, a former bar and lounge designed to look like a prison inside the Bentley Hotel at 510 Ocean Dr. And it was the owner of that hotel, prominent South Florida developer Riccardo Olivieri, who would later commission him to create his colossal Jacques Cousteau.

Olivieri, an Italian businessman now in his 60s, was not only a developer but also an art-lover who adorned his Miami Beach buildings with designer materials, fine paintings, and pricey sculptures. In 2003 his largest South Beach development, the Bentley Bay condo towers at 520 and 540 West Ave., was under construction and he wanted the project to reflect his artistic taste and make a bold statement.

Familiar with Omar Ali’s workmanship, and having already seen a miniature version of Ali’s Jacques Cousteau briefly on display in his Ocean Drive hotel, Olivieri decided that a 25-foot version of the artwork would perfectly compliment the Bentley Bay’s sail-shaped condo towers and reflect the development’s distinct nautical theme. And of course, placed atop the stairwell tower rising above the condo’s multistory parking garage, the sculpture would be visible to every South Beach visitor coming across the MacArthur Causeway, turning the artwork, and the Bentley Bay, into a Miami landmark.

According to Ali’s records, contracts were drawn up in July 2004 and Olivieri agreed to pay him $60,000 to design and construct the full-size Jacques Cousteau piece. The price tag mostly reflected the market cost of stainless steel, heavy-duty equipment required for the job, and labor. Upon completion, Olivieri was to arrange for transportation of the 9000-pound sculpture by barge across Biscayne Bay and have it hoisted by crane into position at the Bentley Bay. Alternatively, the sculpture would cross the bay by helicopter, if consulting engineers felt that would be more practical.

Great blue heron at Ali’s bayfront studio workshop.

What Ali didn’t know at the time, however, was that a pending foreclosure hearing on the Bentley Bay had forced Olivieri’s company, Florida Development Associates, to file for bankruptcy four months before signing the contract with him. Why Olivieri entered into an agreement with Ali in the midst of financial difficulties is unclear. BT’s efforts to contact him for comment were unsuccessful.

By the time Ali learned of the bankruptcy, a few weeks after signing the contract, he had already spent a $5000 deposit from Olivieri and had invested a few thousand dollars of his own money on materials and equipment. He also found that Olivieri had become impossible to reach, and Ali was left wondering if he should even continue work on his sculpture, or if he’d ever be able to recoup his expenses should the agreement fall apart.

The bankruptcy case came before a federal judge in August 2004, and Ali’s agreement with Olivieri was among the contractual obligations the judge ordered to be honored. Moreover, to account for the rapidly increasing price of stainless steel, an amended contract for $80,000 was signed and Ali was instructed to complete his sculpture within 120 days. He received payment in full, hired several workers, and on December 21, 2004, after almost six months of meticulous planning and labor, his sweeping, 25-by-19-foot Jacques Cousteau sculpture, complete with sharks, a shark cage, and abstract representations of waves and sails, stood ready on the concrete patio outside his house.

But a year and half would pass without anyone from the Bentley Bay coming to pick it up. According to Ali, whenever he would call the attorney representing the Bentley’s interests at the time, the lawyer would cite issues with Miami Beach permits relating to the artwork’s installation as reasons for the delay. “They never showed me any proof that they contacted the city,” Ali complains, “and they never asked me for my drawings or sent an engineer to discuss the installation and to draft engineering papers.” Those papers, he says, would have been necessary for the city to determine whether installation was permissible.

Over time it became clear that no one was going to collect the sculpture. The problem, however, was that Ali couldn’t sell it. Technically it didn’t belong to him, since the Bentley Bay had already paid for it. Selling it, he surmised, could put him in the position of having to repay the Bentley Bay should they suddenly decide they wanted it.

Airplane wing bench.

Ali went through a string of lawyers to see if he could regain legal ownership but, he says, three and a half years passed with little communication and no progress. The sculpture remained on Ali’s property, requiring upkeep and safety preparations with each hurricane season to prevent the piece from being destroyed or toppling over onto his house.

Frustrated, Ali drafted a demand letter to the Bentley Bay’s attorneys, threatening legal action and citing the costs he was incurring for storage, maintenance, labor, attorney fees, and more. All this, he asserted, added up to at least $300,000. Ali did not expect to receive monetary damages, but he hoped at least to provoke the Bentley Bay into giving him a legal document restoring his ownership rights to the sculpture — which he claims actually cost him $120,000 in total, $35,000 more than he received in payment.

When he didn’t get a response, he hired what he calls an “honest lawyer,” a Miami attorney named William Sumner Scott, who managed to get results where others had failed. “Perhaps Omar’s letter softened them up a bit and they realized just how bad this could get for them,” Scott says of the Bentley’s legal team. “I simply presented an offer and we negotiated back and forth until we worked it out. It was definitely a heavy-duty negotiation, though.”

To Ali’s surprise, just three weeks later, in October 2008, the Bentley Bay gave him what he needed, a court order signed by federal Judge A. Jay Cristol granting him full ownership rights to Jacques Cousteau, with a stipulation that he “shall not have any further claim” against the Bentley Bay. “I could have pressed my case and tried to get more money from them,” Ali says, “but I was happy not to give them the sculpture in the end. They might have chopped it up and sold it for scrap.”

“The challenge now,” he says, “is to find a buyer. I’m trying to sell it to collectors in Abu Dhabi, where there’s a huge art market, because honestly, good public art doesn’t exist in Miami.”

Of the hundreds of publicly displayed works of art countywide, he points out, hardly any are known outside of the Miami area, and very few are memorable to most locals. “Cheap art is unhealthy,” Ali says. “People are losing trust in artists, and it’s because of all the bad art that’s around.”

Jet engine chair.

Regarding his own work, he refuses to show in galleries because he rejects the commission structure most of them use. “They take half your blood,” he says, and he simply won’t “give [his] life to them.” But with little in the way of commissioned work, lack of exposure is a major issue for Ali.

Still, he can’t imagine doing anything else but create art: “When you love something, you do your best work.” And his best work is all around him. “I’ve always lived in my studio,” he says. “I love to have my tools next to my bed. When I can’t sleep, I get up and make something. Creating things relaxes me.”

He has about 50 cherished pieces he holds onto like offspring, ranging from representational to abstract. “If someone loves them enough to pay the high price,” he says, “I’ll sell them. Otherwise, when I die, I want them all thrown into the ocean.”

Omar Ali’s work inhabits a creative realm where design and fine art co-exist, where the boundaries between form and function tend to blur, where imagination knows no limits. But the enchantment Ali sells comes at a price few art aficionados are able to pay. “Since I’ve been here in the U.S.,” he says, “I’ve been surviving, that’s all, doing small practical jobs here and there.” He’d like to think that the quality of his work will someday be recognized, and that he will once again be able to make a decent living from it.

As for his Jacques Cousteau, he’s holding out hope that it will find a permanent home where it can be appreciated. If not, he’ll commit it to the watery world of its French namesake. He’ll have it sent to the bottom of the Atlantic.

With a trace of heartache in his voice, Ali turns to the quivering waters of Biscayne Bay stretched out before him, finally puts his unlit cigarette back in the pack, and mutters, “It’s written in my will.”

Read this article on the Biscayne Times website.

Newspaper PDF available here.

This is a great, I love the ant forklift and have seen it in person. I would like to know where it is currently located.

If anyone knows the location email me at info@forklifttrader.com

Thank you

Michael

LikeLike